By Lisa Hartwig

Lisa is the mother of 3 gifted children and lives outside of San Francisco.

I gave my 13-year-old daughter makeup for Christmas. I slipped powder, a makeup brush and tinted lip gloss in her stocking. At the time, I was aware of the message I might be sending, but I wanted her to stop raiding my makeup drawer when her friends come over. I didn’t want to take responsibility for the purchases, so they went into her stocking. Santa still fills the stockings.

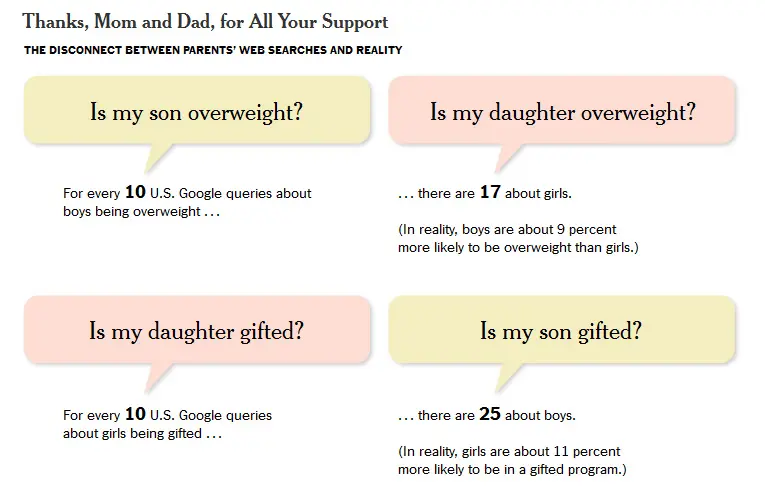

I might have forgotten about my Christmas dilemma if I hadn’t read the New York Times op-ed piece “Google, Tell Me. Is My Son a Genius?” The author reviewed Google searches that used the words son or daughter. According to the author, parents are 2 ½ times more likely to ask “Is my son gifted?” than “Is my daughter gifted?” On the other hand, parents are much more likely to initiate searches relating to their daughters’ appearance. The piece ends with the question “How would American girls’ lives be different if parents were half as concerned with their bodies and twice as intrigued by their minds?”

I think the author makes some assumptions which cause me to question the fairness of his final question. But the article got me thinking about my daughter’s Christmas gifts. Every time I support my daughter’s need to look beautiful, I go through mental gymnastics. I know that she operates in a world where girls are judged more by their ability to entice and nurture rather than to lead and achieve. Any additional attention I pay to her looks or demeanor seems to further that imbalance. But I shouldn’t have to balance one against the other. I want her to be proud of her intellect and her appearance. It’s just that the world is so clearly rewarding her for one, I feel like it’s my job to reinforce the other.

It starts at birth. Consider Jennifer Siebel Newsom, the writer and director of “Miss Representation,” a film that exposes the mainstream media’s message that a woman’s value and power lie in her youth, beauty and sexuality and not in her capacity as a leader. As an advocate for women and the wife of Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom, Ms. Newsom received gifts from the White House upon the birth of her children. She received a “Future President” t-shirt when she gave birth to her son. She received no such gift when her daughter was born.

If you think traditional news outlets do a better job of finding the balance, consider the obituary written by the New York Times upon the death of the brilliant rocket scientist Yvonne Brill on March 27, 2013. The lede read:

She made a mean beef stroganoff, followed her husband from job to job and took eight years off from work to raise three children. ‘The world’s best mom,’ her son Matthew said.

Don’t get me wrong, I want my daughter to find love and raise a family if she chooses. I will be happy if she learns to cook. But I would feel better about communicating my wishes to her if I knew that Robert Oppenheimer made great pancakes and was devoted to his family.

To complicate things, my daughter has a curvy figure and hair whose volume approaches that of a country western singer. So, on top of the makeup, I worry about whether the current fashion of skinny jeans and short shorts will prevent people from seeing her as a leader. All her life, I’ve been telling my daughter to exercise her own judgment and ignore the opinions of others—except if people think the leggings and Abercrombie t-shirt she’s wearing make her look too sexy. Then, she should change her clothes.

Despite my attempts to balance the messages my daughter receives, she has internalized the idea that female power is bad.

A male classmate gave a presentation on social groups in the school. Her group was identified by their name brand clothing. She felt that the description was unflattering; and she felt attacked, so she approached the boy after class.

“Why do you hate me?” she asked.

“I don’t hate you,” he said. “I hate what you represent.”

“What do I represent?”

“Social power.”

My daughter came home that evening convinced that he had called her a “mean girl.” In her mind, social power equates to mean girl status. I think if I asked most people, they would say that power cannot be trusted to a 13-year-old girl. To those people, I need to ask: why not?

We can’t forget that there is some power in how women (and men) look. While taking a negotiation class in law school, one of my male classmates confessed that he had a hard time negotiating opposite a beautiful woman. Advantage: beauty and brains.

As the mother of a gifted girl, I would like her to grow up believing that intellectual ability, power and more traditionally feminine attributes like beauty and a nurturing character are not mutually exclusive. The problem is that no matter which of these attributes I am reinforcing at any given time, I am still reacting to stereotypes. Luckily, my daughter is rather strong willed. My reactions become background noise to her truth. At 13, I am confident that she has the ability to think for herself. All those arguments I have lost over the years when going head to head with her are finally paying off.

Have you struggled with this concept while raising a gifted girl? Please share your experience in the comment section below.