By Lisa Hartwig

Lisa is the mother of 3 gifted children and lives outside of San Francisco.

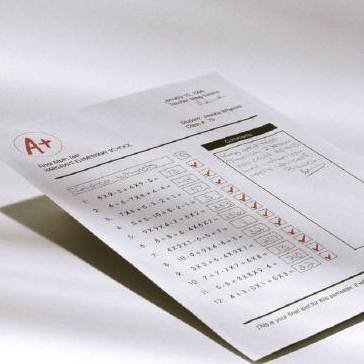

My oldest son didn’t get his first letter grade until he was a senior in high school. His elementary and middle schools did not give grades. In high school, the students only received a single GPA. His assessments were in the form of red lined papers or handwritten comments. By the time he received his first letter grade in the fall of his senior year of high school, it was too late to make any difference; the letters had no meaning and they did not motivate him.

My oldest son didn’t get his first letter grade until he was a senior in high school. His elementary and middle schools did not give grades. In high school, the students only received a single GPA. His assessments were in the form of red lined papers or handwritten comments. By the time he received his first letter grade in the fall of his senior year of high school, it was too late to make any difference; the letters had no meaning and they did not motivate him.

Despite the lack of external grade motivation, my son worked hard and did very well in middle school and high school. He didn’t start that way. In elementary school, he daydreamed. He did only what was required of him in the classroom and no more. I had to ask myself, how did my oldest son go from a daydreaming 5th grader to the top of his high school class without the hammer or carrot of a letter grade? Where did he find the motivation to do well in school?

While looking for an answer, I ran across an article in the November 2012 edition of Scientific American Mind. According to this article, motivation is derived from three critical elements: Autonomy, Value and Competence. Research suggests that you will have more motivation if you feel in charge, feel capable and find meaning in the activity. With this new framework, I thought about my son’s last 8 school years.

In elementary school, I felt as though I had to do a lot of prodding because he showed so little initiative. I didn’t allow him to have autonomy. So, that particular element had to be satisfied elsewhere. The second element, value, had to come from the rewarding feeling of a job well done—right? He didn’t agree. He found no satisfaction in an error-free worksheet. That element also had to come from somewhere else. All I had to work with were his feelings of competence. Unfortunately, he felt most competent when doing work he could master quickly, and he shrank from more difficult challenges. Somehow, I needed him to get out of his comfort zone.

So, I know it wasn’t the grades or my parenting that provided the catalyst for my son’s change in behavior. What made the difference? I talked to my son and asked him how he developed the motivation to excel at school. His comments all focused on how his learning experience changed.

Project Based Learning

Project based learning gave my son a sense of autonomy and imbued his work with value. Allowing my son to have a choice in designing a project and the ability to display his unique vision was the key to helping him find meaning in his work. For example, my son designed and built a scale model of a solar house in 6th grade. The project spanned math and science. He used angle geometry to compute ideal overhangs and created a budget for the construction. He studied how the location of the sun in the sky varies in different places and times. He even tested the effectiveness of his design at the Pacific Energy Center‘s heliodon in San Francisco. 7 years later, my son still has the project in his bedroom.

Inspiring Teachers

How do you get a child to value information that he perceives has nothing to do with his day to day life? You either help him find meaning or introduce him to someone who finds it incredibly meaningful. My son’s history teacher was so passionate about the colonists that he would pound on desks and turn over chairs during a lesson. Who knew the puritans could elicit so much passion? His middle school writing teacher, an aspiring novelist himself, provided intriguing, open-ended character prompts as jumping off points for student work. While the teacher provided the inspiration, my son created work that was all his own. His self-evaluation said it all:

How do you get a child to value information that he perceives has nothing to do with his day to day life? You either help him find meaning or introduce him to someone who finds it incredibly meaningful. My son’s history teacher was so passionate about the colonists that he would pound on desks and turn over chairs during a lesson. Who knew the puritans could elicit so much passion? His middle school writing teacher, an aspiring novelist himself, provided intriguing, open-ended character prompts as jumping off points for student work. While the teacher provided the inspiration, my son created work that was all his own. His self-evaluation said it all:

“When I’m writing on my own, my work is my own. My writing belongs to my world, slowly weaving meaning in the threads of my life… My god, I’m building a world, not a string of imitations.”

Meaningful Feedback

The third element, competence, was enhanced by the feedback provided by the teachers. In the detailed written evaluations by his teachers, my son discovered that he was admired for the generosity he showed his classmates as he shared insights and techniques. He was celebrated for his curiosity and ingenuity. When he received constructive criticism, he knew what to do to improve, increasing his sense of accomplishment and at the same time giving him a sense of control over his progress. These words of encouragement and criticism did more for him than an A. His confidence grew with each evaluation.

We all know that the process of learning can be inherently motivating, but as parents, we feel that we have little influence over the process. So, we focus on outcomes. But we do have some influence over what classes they take and why. We can choose to talk about what they got on a test or how they felt about what they were learning. I was put to the test when my son wanted to learn how to perform on the trapeze instead of taking the AP prep class and exam. He’s still performing on the trapeze in college and decided to stop taking math classes. Despite my misgivings, I hope that by allowing him to choose classes and activities that he values and that make him feel competent, he will end up motivated, productive and happy.

What motivates your kids? Please share in the comment section below.